[UPDATE 1/6/21: I no longer support spending money on products that benefit Zak S, or giving him positive attention and connection. The short version is that I find credible claims that he has engaged in unacceptable behavior and not made up for it. For more detail, see

here for the core of the accusations. To get Zak's side of things, he maintains this

separate blog from his main one to post updates on the legal status of these complaints.

Please consider these claims and make your own decision on their validity, and the implications thereof, before either supporting or shunning Zak.]

Previous Posts

Introduction

I want to start out our trip by taking a detailed look at the poster children of published campaign settings: the 2E boxed sets, and the worlds they detailed.

You’ll notice as we go that I do not much talk about Forgotten Realms, Greyhawk, or Dragonlance. It’s not that they aren’t lovely settings, and as

+Charles Akins pointed out to me on Google+, they are far and away the most popular settings in D&D history, what with their novels and game tie ins and representation in later editions and so forth. So why no love from me in this post?

Well, a few reasons. First, those three settings are all pretty close to “standard D&D” in terms of what the world is like, what you do there, and what you can expect. Dragonlance veers a bit away from that, but not a ton. Second, they all predate the explosion of purposely made “Campaign Settings” in second edition and all come across as pretty much “let’s take my home campaign world and clean it up for publication.” Third, and here I’m showing my bias, the kind of D&D stuff being put out that I enjoy these days is mostly OSR stuff. OSR types who make that stuff tend to have fond places in their hearts for Spelljammer, Planescape, Dark Sun, et cetera, and usually less enthusiasm for those settings I’m leaving out. I am interested in figuring out the common thread between “tastes of people who make great stuff” and “what was in these campaign settings” so that I can make great stuff. The stuff that is great in those “standard” settings seems to pretty much just be an accumulation of detail.

So anyway, what I’m going to do here is highlight what was good, bad, and mixed about these settings, with a bit of explanation and some examples. In the next post, we’ll look at settings I know from the OSR and try to use the same good/bad/mixed characteristics we derive for the 2E settings here.

The Good

There’s a few things that I think made the 2E settings so imaginatively “grabby”. I had some help from Google+ folks to come up with these, and I’d be happy to hear any more ideas in the comments. Anyhow, here’s the stuff I’ve identified that made the 2E settings work:

Rules Do Not Equal Setting:

+Zak Smith made the excellent point that D&D was (and is) the most popular RPG of all time. So the mere fact that you could do something

new while still using the rules you knew and that were super well supported was a big draw. It made the cost of entry pretty low, and it allowed the settings to build on existing imaginary capital - you already know what a halfling is, so when I tell you that

these halflings are cannibals, that has more resonance than if I just say “short people with hairy feet that want to eat you”.

Strong Theme:

+Ramanan S pointed out that for the most part, each setting had a strong central theme. Ravenloft = Gothic Horror. Dark Sun = Harsh Desert Survival. Planescape = Abstract Made Physical. Et cetera. This ties into the above point about being able to “do something different”. These settings had strong “elevator pitches” which made GMs and players want to find out more, to do stuff in a world like that. I have to imagine that such strongly stated themes made the work of any writers and designers and artists easier, as it gave them something clear to work with.

Strong Art Direction & Good Art: Speaking of which, how about that art, huh? I mean, the Planescape boxed set was just about

entirely illustrated by Tony Diterlizzi, and for most of the line, he at least did art direction, if not most of the illustration himself. Dark Sun without Brom would be a very different and less resonant thing. I think a lot of these settings hit a sweet spot between the early days of “whatever art we can afford and that fits” and the more recent “we have one, big cohesive brand to maintain here”. Also, "art direction" is possibly a misnomer, since the relationship was more collaborative between artists and writers in the best examples.

Genuine Difference from “Standard D&D”: These settings gave you stuff that really was different from a pseudo-european pseudo-medieval setting full of orcs and goblins. Sure, a lot of the same stuff got ported around (like orcs and goblins), but most of the settings had

something different going on. Especially those settings that OSR types hold up these days as “why don’t we have stuff like this anymore?” Planescape, Dark Sun, Ravenloft, even Al-Qadim all give you new kinds of fantasy to get excited about and offer a change of pace to folks feeling jaded with D&D’s traditional flavor.

Play About New Things: Really this is a continuation of the above point, but I think it warranted breaking out. The point above is more about the theme or flavor being enticing or exotic or just new. This one is the fact that once you make a character in this interesting new world and sit down to play, you actually

do different things. While dungeons were pretty much assumed in every setting, standard dungeoncrawling was not really presented as the default play style in these new settings. Some settings did this better than others, but all of them at least held out the promise that you weren’t just dungeoncrawling with different clothes on and killing different colored orcs.

Mechanical Differentiation: This one is in a bit of tension with the above

Rules Do Not Equal Setting, but I think both contributed to settings “working”. It’s also building on the above two points about difference and new things. The base was D&D, so you didn’t need a whole different game, but there were enough mechanically new bits to make it actually interesting and new. New classes, character races, kits, spells, and so forth supported the different approaches you were supposed to take. I’m not saying they always got this one totally right, but it was there, and I think it contributed to the distinctness of the settings.

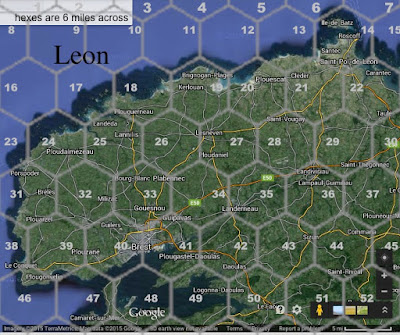

Maps: Man I had a ton of fun pouring over the maps that came with the 2E campaign settings, and more than once they led directly to interesting play for my group. There may have been more maps and more detail than was strictly necessary, but they really made the settings feel like “places” in a way that strictly tactical local maps of dungeons and the like don’t.

The Bad

I was actually pleasantly surprised by how few things I could categorize as outright

bad with the settings in question. In fact, I only felt like there were two categories that aren’t at least mixed. Those two categories are

preetttty big deals, though.

Padding: This is the elephant in the room when we’re praising these settings. Maybe it was writers paid by the word, maybe it was a misguided attempt to write pseudo-fiction, or maybe a belief that if something is not at least X pages, it’s not a real book. I don’t know. What I do know is that all of that good stuff above is weighed down in just loads of extraneous crapadoodle. Mundane details, over explanation, stuff with little possible relevance to adventures or players, snippets of mediocre fiction, the list goes on. It is perhaps unfair to lay too much retroactive blame for this, but we can certainly do better.

Moralizing: After the satanic panic of the 80’s and just the general trend of D&D products more often bought by parents for their kids, 2E ended up with a definite “epic fantasy about good guys versus bad guys” vibe going on. From a

recent post by Jeff Grubb, I think that having explicit good guys and bad guys was actually a requirement for settings. That post, by the way, is a pitch for a never-made 2E setting, and provides an excellent window on what went on behind the scenes to give us the settings we’re talking about today. Now, don’t get me wrong: moral underpinnings to stories, being the good guys, smiting evil, these are all good fun. I’m not saying I wish all of these settings were nihilistic moral wastezones. It is more that the kind of simplistic, watered down morality pushed by the settings at this time is kind of boring. Perhaps more importantly, as Zak

pointed out long ago, roguish folks can more easily self-direct into adventure, whereas good guys have to be more reactive almost by definition. So overly strong statements of where the evil is and how it should be fought end up robbing the players of agency.

The Mixed

So, there were a number of things I identified as inherent to the presentation of these settings that really seem like coins with two sides. Elements that had both positive and negative aspects. The good news for us looking back is that for many of them it’s comparatively easy to identify what was good and focus on that without bringing in what was bad.

Jamming/Design by Committee: This is an interesting topic that came up in the

Google+ discussion that prompted this post (if you can’t see the post, send me a message on G+ and I’ll add you to my circles). Since these settings were the products of teams of designers, writers, artists, et cetera, we end up seeing both the good and the bad sides of creative collaboration. You get people riffing on each other’s ideas, doubtless creating some stuff that was better than the sum of its parts. But then you also get the decision to pull back from more out-there or funky stuff that might be more creative or imaginatively rich.

Constraints of Standard 2E: On the one hand, working within requirements can produce fun creative constraints, like “Okay, we have to have halflings, but what should they be like? How about cannibals!” On the other hand, do Elves really do much for Al-Qadim? What about having the same kind of spellcasting in a world of Gothic Horror as in a cosmopolitan city at the center of the multiverse? Sometimes the requirement to include the “standard” rules/races/classes made for some odd fits.

Detailed NPCs/World Events: So, having interesting people, events, and places is sort of exactly the reason for a campaign setting. On the other hand, when you have pages and pages on super high level NPCs, plus world events/plots with detailed descriptions of how they will unfold, you start getting into some boring railroady stuff. Looking back to our definition of the bad kind of special snowflake setting, I’d say the NPCs, behind the scenes plotlines, and major world events are bad to the degree that they become

frozen and are no longer malleable to player interaction or will.

Sheer Depth: The good part of this one is that there was a lot of material to work with. You could comb through a setting until you found something that grabbed you and build an adventure or even a campaign around that. If you took the time to soak it all in, you had a lot of context for when you needed to improvise things that fit the world. On the other hand, that same amount of depth could easily become minutiae, boring and unuseful facts, and stuff with no bearing on play. It could come to feel like homework to really get to know a setting. That’s when you start getting into the padding from above.

Nostalgia: Okay, so sure, some of the appeal for these settings might be that I (and a lot of current OSR folks) “grew up” with them in one sense or another, and we’re looking at these settings through rose colored glasses. So maybe there’s not as much good about them as we think there is. On the other hand, only remembering the gems among the kruft is not a bad thing. I sometimes get the urge to do hyper-concentrated distillations of settings, kind of like I did with

Middenheim, but then I realize that is time and energy probably better spent on creating my own stuff.

Next Time

In the next post, I’ll apply these categories to some OSR settings I’m familiar with. There’s not nearly as many published settings, but there’s a plethora of great settings from OSR blogs. Spoiler alert: they tend to display the good qualities identified above while avoiding the bad.